NGORONGORO CONSERVATION AREA

The Ngorongoro Conservation Area also protects Oldurai or Olduvai Gorges

, situated in the plains area. It is considered to be the seat of

humanity after the discovery of the earliest known specimens of the

human genus, Homo habilis as well as early hominidae, such as Paranthropus boisei.

The Olduvai Gorge is a steep-sided ravine in the Great Rift Valley, which stretches along eastern Africa. Olduvai is in the eastern Serengeti Plains in northern Tanzania

and is about 50 kilometres (31 mi) long. It lies in the rain shadow of

the Ngorongoro highlands and is the driest part of the region.The gorge is named after 'Oldupaai', the Maasai word for the wild sisal plant, Sansevieria ehrenbergii.

The Olduvai Gorge is a steep-sided ravine in the Great Rift Valley, which stretches along eastern Africa. Olduvai is in the eastern Serengeti Plains in northern Tanzania

and is about 50 kilometres (31 mi) long. It lies in the rain shadow of

the Ngorongoro highlands and is the driest part of the region.The gorge is named after 'Oldupaai', the Maasai word for the wild sisal plant, Sansevieria ehrenbergii.

It is one of the most important prehistoric sites in the world and research there has been instrumental in furthering understanding of early human evolution. Excavation work there was pioneered by Mary and Louis Leakey

in the 1950s and is continued today by their family. Some believe that

millions of years ago, the site was that of a large lake, the shores of

which were covered with successive deposits of volcanic ash. Around 500,000 years ago seismic

activity diverted a nearby stream which began to cut down into the

sediments, revealing seven main layers in the walls of the gorge.

Wildlife

Approximately 25,000 large animals, mostly ungulates, live in the crater.

Large mammals in the crater include the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis michaeli), the local population of which declined from about 108 in 1964-66 to between 11-14 in 1995, the African buffalo or Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer), and the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius). There also are many other ungulates: the blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) (7,000 estimated in 1994), Grant's zebra (Equus quagga boehmi) (4,000), the common eland (Taurotragus oryx), and Grant's (Nanger granti) and Thomson's gazelles (Eudorcas thomsonii) (3,000). Waterbucks (Kobus ellipsiprymnus) occur mainly near Lerai Forest.

Approximately 25,000 large animals, mostly ungulates, live in the crater.

Large mammals in the crater include the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis michaeli), the local population of which declined from about 108 in 1964-66 to between 11-14 in 1995, the African buffalo or Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer), and the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius). There also are many other ungulates: the blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) (7,000 estimated in 1994), Grant's zebra (Equus quagga boehmi) (4,000), the common eland (Taurotragus oryx), and Grant's (Nanger granti) and Thomson's gazelles (Eudorcas thomsonii) (3,000). Waterbucks (Kobus ellipsiprymnus) occur mainly near Lerai Forest.

Absent are giraffe, impala (Aepyceros melampus), topi (Damaliscus lunatus), oribi (Ourebia oribi), crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus).

cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus raineyi), East African wild dog (Lycaon pictus lupinus), and African leopard (Panthera pardus pardus) are rarely seen. Spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) have been the subject of a long-term research study in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area since 1996.

Although thought of as "a natural enclosure" for a very wide

variety of wildlife, 20 percent or more of the wildebeest and half the

zebra populations vacate the crater in the wet season, while Cape

buffalo (Syncerus caffer) stay; their highest numbers are during the rainy season.

Since 1986, the crater's wildebeest population has fallen from 14,677 to 7,250 (2003-2005).The numbers of eland and Thomson's gazelle also have declined while the

buffalo population has increased greatly, probably due to the long

prevention of fire which favors high-fibrous grasses over shorter, less

fibrous types.

Serval (Leptailurus serval) occurs widely in the crater.

Lake Magadi, a large lake in the southwest of the crater, is often inhabited by thousands of mainly lesser flamingoes.

The crater has one of the densest known population of lions, numbering 62 in 2001.

The crater has one of the densest known population of lions, numbering 62 in 2001.

A side effect of the crater being a natural enclosure is that the

lion population is significantly inbred. This is due to the very small

amount of new bloodlines that enter the local gene pool, as very few

migrating male lions enter the crater from the outside. Those who do

enter the crater are often prevented from contributing to the gene pool

by the crater's male lions, who expel any outside competitors.

Long-term data imply that lions in the crater were struck by four deadly disease outbreaks between 1962 and 2002.Drought in 1961 and rains throughout the 1962 dry season caused a massive build-up of blood-sucking stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans)

by May 1962. They drained blood and caused painful skin sores that

became infected, causing lion numbers to crash from 75-100 to 12. The

population recovered to around 100 by 1975 and remained stable until

1983, when a persistent decline began. Numbers have generally remained

below 60 animals since 1993, reaching a low of 29 in 1998. In 2001, 34

percent of the lion population died between January and April from a

combination of tick-borne disease and canine distemper.

The lion population is also influenced to some extent by the

takeover of prides by incoming males, which typically kill small cubs.The biggest influence, however, appears to be disease, particularly canine distemper.

Ngorongoro

Conservation Area is in northern Tanzania. It’s home to the vast,

volcanic Ngorongoro Crater and “big 5” game (elephant, lion, leopard,

buffalo, rhino). Huge herds of wildebeests and zebras traverse its

plains during their annual migration. Livestock belonging to the

semi-nomadic Maasai tribe graze alongside wild animals. Hominin fossils

found in the Olduvai Gorge date back millions of years.

Outside Ngorongoro Crater

The

Ngorongoro Conservation Area has a healthy resident population of most

species of wildlife. The Ndutu Lake area to in the west of the

conservation area has particularly strong cheetah and lion populations. Common in the area are hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus), spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), and jackals.The population of African wild dog may have declined recently. Servals occur widely on the plains to the west of the Ngorongoro Crater.

The annual ungulate migration passes through the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, with 1.7 million wildebeest, 260,000 zebra,

and 470,000 gazelles moving south into the area in December and moving

north in June. This movement changes seasonally with the rains, but the

migration traverses almost the entire plains in search of food.

The annual ungulate migration passes through the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, with 1.7 million wildebeest, 260,000 zebra,

and 470,000 gazelles moving south into the area in December and moving

north in June. This movement changes seasonally with the rains, but the

migration traverses almost the entire plains in search of food.

The oldest known elephant to give birth to twins is found in Tarangire. A recent birth of elephant twins in the Tarangire National Park of Tanzania is a great example of how the birth of these two healthy and thriving twins can beat the odds.

Home to more than 550 bird species, the park is a haven for bird enthusiasts. The park is also famous for the termite mounds that dot the landscape. Those that have been abandoned are often home to dwarf mongoose. In 2015, a giraffe that is white due to leucism was spotted in the park. Wildlife research is focused on African bush elephant and Masai giraffe.

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit

LAKE MANYARA NATIONAL PARK

Lake Manyara is the seventh-largest lake of Tanzania by surface area, at 470-square-kilometre (180 sq mi). It is a shallow, alkaline lake in the Natron-Manyara-Balangida branch of the East African Rift in Manyara Region in Tanzania.[2].The northwest quadrant of the lake (about 200 sq, km.) [3] is included within Lake Manyara National Park and it is part of the Lake Manyara Biosphere Reserve, established in 1981 by UNESCO as part of its Man and the Biosphere Programme.

Lake Manyara is the seventh-largest lake of Tanzania by surface area, at 470-square-kilometre (180 sq mi). It is a shallow, alkaline lake in the Natron-Manyara-Balangida branch of the East African Rift in Manyara Region in Tanzania.[2].The northwest quadrant of the lake (about 200 sq, km.) [3] is included within Lake Manyara National Park and it is part of the Lake Manyara Biosphere Reserve, established in 1981 by UNESCO as part of its Man and the Biosphere Programme.

Serengeti

National Park, in northern Tanzania, is known for its massive annual

migration of wildebeest and zebra. Seeking new pasture, the herds move

north from their breeding grounds in the grassy southern plains. Many

cross the marshy western corridor’s crocodile-infested Grumeti River.

Others veer northeast to the Lobo Hills, home to black eagles. Black

rhinos inhabit the granite outcrops of the Moru Kopjes.

Serengeti

National Park, in northern Tanzania, is known for its massive annual

migration of wildebeest and zebra. Seeking new pasture, the herds move

north from their breeding grounds in the grassy southern plains. Many

cross the marshy western corridor’s crocodile-infested Grumeti River.

Others veer northeast to the Lobo Hills, home to black eagles. Black

rhinos inhabit the granite outcrops of the Moru Kopjes.

Lion:

the Serengeti is believed to hold the largest population of lions in

Africa due in part to the abundance of prey species. More than 3,000

lions live in this ecosystem.

Lion:

the Serengeti is believed to hold the largest population of lions in

Africa due in part to the abundance of prey species. More than 3,000

lions live in this ecosystem.

African leopard: these reclusive predators are commonly seen in the Seronera region but are present throughout the national park with the population at around 1,000.

African bush elephant: the herds have recovered successfully from population lows in the 1980s caused by poaching, numbering over 5,000 individuals, and are particularly numerous in the northern region of the park.

Eastern black rhinoceros: mainly found around the kopjes in the centre of the park, very few individuals remain due to rampant poaching. Individuals from the Masai Mara Reserve cross the park border and enter Serengeti from the northern section at times. There's currently a small but stable population of 31 individuals left in the park.

Other mammals include aardvark, aardwolf, bat-eared fox, ground pangolin, crested porcupine, three species of hyraxes and cape hare.

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit together with Maasai Mara National Reserve and a lion stronghold in East Africa-

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit together with Maasai Mara National Reserve and a lion stronghold in East Africa-

The administrative body for all parks in Tanzania is the Tanzania National Parks Authority. Myles Turner was one of the park's first game wardens and is credited with bringing its rampant poaching under control. His autobiography, My Serengeti Years: The Memoirs of an African Game Warden,

provides a detailed history of the park's early years.

The African Network for Animal Welfare sued the Tanzanian government in December 2010 at the East African Court of Justice in Arusha

to prevent the road project. The court ruled in June 2014 that the plan

to build the road was unlawful because it would infringe the East African Community Treaty

under which member countries must respect protocols on conservation,

protection, and management of natural resources. The court, therefore,

restrained the government from going ahead with the project.

The African Network for Animal Welfare sued the Tanzanian government in December 2010 at the East African Court of Justice in Arusha

to prevent the road project. The court ruled in June 2014 that the plan

to build the road was unlawful because it would infringe the East African Community Treaty

under which member countries must respect protocols on conservation,

protection, and management of natural resources. The court, therefore,

restrained the government from going ahead with the project.

Kilimanjaro

National Park, in the East African country of Tanzania, is home to the

continent's highest mountain, snowcapped Mt. Kilimanjaro. Around the

base of its tallest peak, relatively accessible hiking trails wind

through rainforest inhabited by colobus monkeys and past the volcanic

caldera of Lake Chala. Approaching the summit of Uhuru Peak, the slopes

steepen and are studded with glacial ice fields.

Kilimanjaro

National Park, in the East African country of Tanzania, is home to the

continent's highest mountain, snowcapped Mt. Kilimanjaro. Around the

base of its tallest peak, relatively accessible hiking trails wind

through rainforest inhabited by colobus monkeys and past the volcanic

caldera of Lake Chala. Approaching the summit of Uhuru Peak, the slopes

steepen and are studded with glacial ice fields.

Fauna

A variety of animals can be found in the park. Above the timberline, the Kilimanjaro tree hyrax, the grey duiker, and rodents are frequently encountered.[3] The bushbuck and red duiker appear above the timberline in places.[3]Cape buffaloes are found in the montane forest and occasionally in the moorland and grassland.[3]Elephants can be found between the Namwai and Tarakia rivers and sometimes occur at higher elevations.[3] In the montane forests, blue monkeys, western black and white colobuses, bushbabies, and leopards can be found.[

The

Mikumi National Park near Morogoro, Tanzania, was established in 1964.

It covers an area of 3,230 km² is the fourth largest in the country. The

park is crossed by Tanzania's A-7 highway.

The

Mikumi National Park near Morogoro, Tanzania, was established in 1964.

It covers an area of 3,230 km² is the fourth largest in the country. The

park is crossed by Tanzania's A-7 highway.

Mahale Mountains National Park lies on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in Kigoma Region, Tanzania. Named after the Mahale Mountains range that is within its borders, the park has several unusual characteristics. First, it is one of only two protected areas for chimpanzees in the country. (The other is nearby Gombe Stream National Park made famous by the researcher Jane Goodall.) The chimpanzee population in Mahale Mountains National Park is the largest known and due to its size and remoteness, the chimpanzees flourish. It also the only place where chimpanzees and lions co-exist. Another unusual feature of the park is that it is one of the very few in Africa that must be experienced by foot. There are no roads or other infrastructure within the park boundaries, and the only way in and out of the park is via boat on the lake.

The Mahale mountains were traditionally inhabited by the Batongwe and Holoholo people, with populations in 1987 of 22,000 and 12,500 respectively. When the Mahale Mountains Wildlife Research Center was established in 1979 these people were expelled from the mountains to make way for the park, which opened in 1985. The people had been highly attuned to the natural environment, living with virtually no impact on the ecology.[2]

Jozani is a village on the Tanzanian island of Unguja (Zanzibar Island). It is located in the southeast of the island, 3.1 miles (5 km) south of Chwaka Bay, close to the edge of the Jozani-Chwaka Bay National Park.[2] It is primarily a farming community of about 800 people.[3] Jozani Village is located 21.7 miles (35 km) south-east of Zanzibar Town off the road leading to Paje, Zanzibar.

Jozani is a village on the Tanzanian island of Unguja (Zanzibar Island). It is located in the southeast of the island, 3.1 miles (5 km) south of Chwaka Bay, close to the edge of the Jozani-Chwaka Bay National Park.[2] It is primarily a farming community of about 800 people.[3] Jozani Village is located 21.7 miles (35 km) south-east of Zanzibar Town off the road leading to Paje, Zanzibar.

It is easily reached by public buses 309 and 310, by chartered taxi or as an organized tour from Zanzibar Town. These tours are often in combination with dolphin observation in Kizimkazi,[4] one of Zanzibar’s oldest settlements with a tiny 12th century mosque open to public.[5] The main road on the island, connecting the west and east coasts of Zanzibar, also connects to Jozani. Besides public bus routes 9, 10 and 13, you can also get here from Zanzibar Town by dala-dala number 309, 310, 324, and 326.[6] Jozani is a small and rural village, situated in the innermost part of the Pete Inlet Bay, immediately south of the Jozani Chwaka Bay National Park. It is one of six rural villages surrounding the park. Residents here depend to a large degree on the Jozani Forest as a source of firewood, hunting, building resources, farming, fishing, and more. The village also operates ecotourism in the Jozani Forest and has constructed a 0.6 mile (1 km) boardwalk through the mangroves at the southern road entrance into the national park. Many villagers work as authorized guides for tours in the southern tip of Jozani Forest.

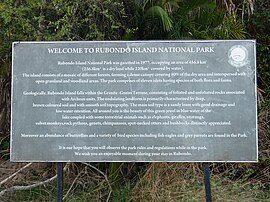

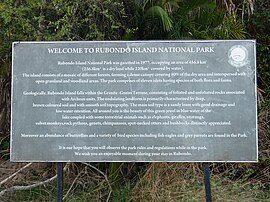

Rubondo Island became a game reserve in 1965, to provide a sanctuary for animals.

Rubondo Island was gazetted as a national park in 1977. Today Rubondo

is uninhabited. Consequently, 80% of the island remains forested today.

The 400 “fisher folk” of the Zinza tribe,

who lived on the island and maintained banana plantations, were

resettled on neighbouring islands and onto the mainland by the

government in the late 1960s.As a rule the court passed sentences of six weeks imprisonment for

unauthorised landings on the island and six months for attempted

poaching (for example, see the story by Idogu on a group of fishermen caught poaching on the island in 1994 at https://www.flickr.com/photos/idogu/819509281/).

Rubondo Island became a game reserve in 1965, to provide a sanctuary for animals.

Rubondo Island was gazetted as a national park in 1977. Today Rubondo

is uninhabited. Consequently, 80% of the island remains forested today.

The 400 “fisher folk” of the Zinza tribe,

who lived on the island and maintained banana plantations, were

resettled on neighbouring islands and onto the mainland by the

government in the late 1960s.As a rule the court passed sentences of six weeks imprisonment for

unauthorised landings on the island and six months for attempted

poaching (for example, see the story by Idogu on a group of fishermen caught poaching on the island in 1994 at https://www.flickr.com/photos/idogu/819509281/).

Over a four-year period (1966–1969) Professor Bernhard Grzimek of the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) released 17 chimpanzees in four cohorts onto Rubondo Island.The first cohort of chimpanzees arrived in Dar es Salaam

aboard the German African Line’s steamship Eibe Oldendorff on 17 June

1966 (Standard Newspaper Tanzania, 1966). The animals had no

rehabilitation or pre-release training. The chimpanzees were all

wild-born and purportedly of West African descent,although there are no records of specific country of origin for the majority of released individuals.The founder chimpanzees had spent varying periods, from 3.5 months to 9

years, in captivity in European zoos or circuses before their release.

The chimpanzees after one year were able to find and eat wild foods and

construct nests for sleeping, and have now reverted to an unhabituated

state characteristic of wild chimpanzees. From 16 founders the population has now grown to around 40 individuals (estimate based on nest counts).

Over a four-year period (1966–1969) Professor Bernhard Grzimek of the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) released 17 chimpanzees in four cohorts onto Rubondo Island.The first cohort of chimpanzees arrived in Dar es Salaam

aboard the German African Line’s steamship Eibe Oldendorff on 17 June

1966 (Standard Newspaper Tanzania, 1966). The animals had no

rehabilitation or pre-release training. The chimpanzees were all

wild-born and purportedly of West African descent,although there are no records of specific country of origin for the majority of released individuals.The founder chimpanzees had spent varying periods, from 3.5 months to 9

years, in captivity in European zoos or circuses before their release.

The chimpanzees after one year were able to find and eat wild foods and

construct nests for sleeping, and have now reverted to an unhabituated

state characteristic of wild chimpanzees. From 16 founders the population has now grown to around 40 individuals (estimate based on nest counts).

In addition to chimpanzees, seven other species were introduced to the island: Roan antelope (Hippotragus equinus) and rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) both now extinct, Suni antelope (Neotragus moschatus), elephants (Loxodonta africana), twelve giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis), 20 black-and-white colobus monkeys (Colobus guereza), and grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus) confiscated from illegal trade; see .

For more information please see the TANAPA website https://www.asiliaafrica.com/chimpanzee-habituation-update-rubondo-island/

Common native fauna include the vervet monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops), sitatunga (Tragelaphus spekei), hippopotamus, genet and bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus).

Rubondo Island can be reached by park boat from two different

locations. One option is the boat from Kasenda, a small village near

Muganza in Chato District. The other option is the boat from Nkome in Geita District.

By airplane, Rubondo Airstrip can be reached with Auric Air or Coastal Aviation.

Rubondo Island can be reached by park boat from two different

locations. One option is the boat from Kasenda, a small village near

Muganza in Chato District. The other option is the boat from Nkome in Geita District.

By airplane, Rubondo Airstrip can be reached with Auric Air or Coastal Aviation.

The annual ungulate migration passes through the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, with 1.7 million wildebeest, 260,000 zebra,

and 470,000 gazelles moving south into the area in December and moving

north in June. This movement changes seasonally with the rains, but the

migration traverses almost the entire plains in search of food.

The annual ungulate migration passes through the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, with 1.7 million wildebeest, 260,000 zebra,

and 470,000 gazelles moving south into the area in December and moving

north in June. This movement changes seasonally with the rains, but the

migration traverses almost the entire plains in search of food.

TARANGIRE NATIONAL PARK

Tarangire National Park is a national park in Tanzania's Manyara Region. The name of the park originates from the Tarangire River that crosses the park. The Tarangire River is the primary source of fresh water for wild animals in the Tarangire Ecosystem during the annual dry season. The Tarangire Ecosystem is defined by the long-distance migration of wildebeest and zebras. During the dry season thousands of animals concentrate in Tarangire National Park from the surrounding wet-season dispersal and calving areas.

Tarangire

National Park is a national park in Tanzania's Manyara Region. The name

of the park originates from the Tarangire River that crosses the park.

The Tarangire River is the primary source of fresh water for wild

animals in the Tarangire Ecosystem during the annual dry season. Wikipedia

Area: 1,100 mi²

Flora and fauna

The park is famous for its high density of elephants and baobab trees. Visitors to the park in the June to November dry season can expect to see large herds of thousands of zebra, wildebeest and cape buffalo. Other common resident animals include waterbuck, giraffe, dik dik, impala, eland, Grant's gazelle, vervet monkey, banded mongoose, and olive baboon. Predators in Tarangire include lion, leopard, cheetah, caracal, honey badger, and African wild dog.The oldest known elephant to give birth to twins is found in Tarangire. A recent birth of elephant twins in the Tarangire National Park of Tanzania is a great example of how the birth of these two healthy and thriving twins can beat the odds.

Home to more than 550 bird species, the park is a haven for bird enthusiasts. The park is also famous for the termite mounds that dot the landscape. Those that have been abandoned are often home to dwarf mongoose. In 2015, a giraffe that is white due to leucism was spotted in the park. Wildlife research is focused on African bush elephant and Masai giraffe.

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit

LAKE MANYARA NATIONAL PARK

Lake Manyara is the seventh-largest lake of Tanzania by surface area, at 470-square-kilometre (180 sq mi). It is a shallow, alkaline lake in the Natron-Manyara-Balangida branch of the East African Rift in Manyara Region in Tanzania.[2].The northwest quadrant of the lake (about 200 sq, km.) [3] is included within Lake Manyara National Park and it is part of the Lake Manyara Biosphere Reserve, established in 1981 by UNESCO as part of its Man and the Biosphere Programme.

Lake Manyara is the seventh-largest lake of Tanzania by surface area, at 470-square-kilometre (180 sq mi). It is a shallow, alkaline lake in the Natron-Manyara-Balangida branch of the East African Rift in Manyara Region in Tanzania.[2].The northwest quadrant of the lake (about 200 sq, km.) [3] is included within Lake Manyara National Park and it is part of the Lake Manyara Biosphere Reserve, established in 1981 by UNESCO as part of its Man and the Biosphere Programme. There are differing explanations for how Lake Manyara got its name. The name Manyara may come from the Maasai word emanyara, which is the spiky, protective enclosure around a family homestead (boma). Possibly the 600 m high rift escarpment hems in the lake, like the enclosure around a Maasai boma[5]. Another theory is that the Mbugwe tribe, who live in the Lake Manyara area, may have given the lake its name based on the Mbugwe word manyero, meaning a trough or place where animals drink water

Lake

Manyara National Park is a protected area in Tanzania's Arusha and

Manyara Regions, situated between Lake Manyara and the Great Rift

Valley. It is administered by the Tanzania National Parks Authority, and

covers an area of 325 km² including about 230 km² lake surface. Wikipedia

Area: 125.5 mi²

Hydrology

The lake is in a closed basin with no outflow. It is fed by underground springs and by several permanent streams and rivers that drain the surrounding Ngorongoro Highlands, but the vast majority of the inflow (over 99%) comes from rainfall. The lake's depth and the area it covers fluctuates significantly. At its maximum, during the wet season, the lake is 40 km wide by 15 km with a maximum depth of 3.7 m. In 2010, a bathymetry survey showed the lake to have an average depth 0.81 m, and a maximum depth of about 1.18 m. In extreme dry periods the surface area of the lake shrinks as the waters evaporate and at times the lake has dried up completely. Lake Manyara is a soda or alkaline lake with a pH near 9.5, and it is also high in dissolved salts. The water becomes increasingly brackish in the dry season as water evaporates and salts accumulate. During dry spells, large areas of mud flats become exposed along the shore. These alkaline flats sprout into grasslands, attracting grazing animals, including large herds of buffalo, wildebeest and zebra.Fish

The main fish species inhabiting the lake are catfish and tilapia. There is a small fishery, but fish only tend to be found near the inflow areas, where salt concentrations are lower. Lake Manyara is the type locality for the endangered fish Oreochromis amphimelas, a species of in the cichlid family, endemic to Tanzania, found in Lake Manyara and a number of other saline lakes with closed basins. Exploitation is prohibited in the parts of Lake Manyara within the National Park and the protected park areas provide important seed stock for the replenishment of fished populations.Birds

Lake Manyara National Park is known for flocks of thousands flamingos that feed along the edge of the lake in the wet season. At times, there have been over an estimated 2 million individuals of various species of water birds. The following table summarizes the most numerous species, according to the Important Bird Areas factsheet: Lake Manyara.

Established: 1960

SERENGETI NATIONAL PARK

The Serengeti National Park is a Tanzanian national park in the Serengeti ecosystem in the Mara and Simiyu regions.It is famous for its annual migration of over 1.5 million white-bearded (or brindled) wildebeest and 250,000 zebra and for its numerous Nile crocodile and honey badger.

Serengeti

National Park, in northern Tanzania, is known for its massive annual

migration of wildebeest and zebra. Seeking new pasture, the herds move

north from their breeding grounds in the grassy southern plains. Many

cross the marshy western corridor’s crocodile-infested Grumeti River.

Others veer northeast to the Lobo Hills, home to black eagles. Black

rhinos inhabit the granite outcrops of the Moru Kopjes.

Serengeti

National Park, in northern Tanzania, is known for its massive annual

migration of wildebeest and zebra. Seeking new pasture, the herds move

north from their breeding grounds in the grassy southern plains. Many

cross the marshy western corridor’s crocodile-infested Grumeti River.

Others veer northeast to the Lobo Hills, home to black eagles. Black

rhinos inhabit the granite outcrops of the Moru Kopjes.

Area: 5,695 mi²

The Maasai people had been grazing their livestock in the open plains of eastern Mara Region, which they named "endless plains," for around 200 years when the first European explorer, Austrian Oscar Baumann, visited the area in 1892.The name "Serengeti" is an approximation of the word used by the Maasai to describe the area, siringet, which means "the place where the land runs on forever".

The first American to enter the Serengeti, Stewart Edward White, recorded his explorations in the northern Serengeti in 1913. He returned to the Serengeti in the 1920s and camped in the area around Seronera for three months. During this time, he and his companions shot 50 lions

Because the hunting of lions made them scarce, the British colonial administration made a partial game reserve of 800 acres (3.2 km2) in the area in 1921 and a full one in 1929. These actions were the basis for Serengeti National Park, which was established in 1951.

The Serengeti gained more fame after the initial work of Bernhard Grzimek and his son Michael in the 1950s. Together, they produced the book and film Serengeti Shall Not Die, widely recognized as one of the most important early pieces of nature conservation documentary.

To preserve wildlife, the British evicted the resident Maasai from the park in 1959 and moved them to the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. There is still considerable controversy surrounding this move, with claims made of coercion and deceit on the part of the colonial authorities.

The park is Tanzania's oldest national park and remains the

flagship of the country's tourism industry, providing a major draw to

the Northern Safari Circuit encompassing Lake Manyara National Park, Tarangire National Park, Arusha National Park and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. It has over 2,500 lions and more than 1 million wildebeest.

The park is Tanzania's oldest national park and remains the

flagship of the country's tourism industry, providing a major draw to

the Northern Safari Circuit encompassing Lake Manyara National Park, Tarangire National Park, Arusha National Park and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. It has over 2,500 lions and more than 1 million wildebeest.

The park is usually described as divided into three regions-

Northern Serengeti: the landscape is dominated by open woodlands (predominantly Commiphora) and hills, ranging from Seronera

in the south to the Mara River on the Kenyan border. Apart from the

migratory wildebeest and zebra (which occur from July to August, and in

November), this is the best place to find elephant, giraffe, and dik dik.

Human habitation is forbidden in the park with the exception of staff for the Tanzania National Parks Authority, researchers and staff of the Frankfurt Zoological Society,

and staff of the various lodges, campsites and hotels. The main

settlement is Seronera, which houses the majority of research staff and

the park's main headquarters, including its primary airstrip.

Human habitation is forbidden in the park with the exception of staff for the Tanzania National Parks Authority, researchers and staff of the Frankfurt Zoological Society,

and staff of the various lodges, campsites and hotels. The main

settlement is Seronera, which houses the majority of research staff and

the park's main headquarters, including its primary airstrip.

History

A group of lions in a tree on the Serengeti prairies.

The first American to enter the Serengeti, Stewart Edward White, recorded his explorations in the northern Serengeti in 1913. He returned to the Serengeti in the 1920s and camped in the area around Seronera for three months. During this time, he and his companions shot 50 lions

Because the hunting of lions made them scarce, the British colonial administration made a partial game reserve of 800 acres (3.2 km2) in the area in 1921 and a full one in 1929. These actions were the basis for Serengeti National Park, which was established in 1951.

The Serengeti gained more fame after the initial work of Bernhard Grzimek and his son Michael in the 1950s. Together, they produced the book and film Serengeti Shall Not Die, widely recognized as one of the most important early pieces of nature conservation documentary.

To preserve wildlife, the British evicted the resident Maasai from the park in 1959 and moved them to the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. There is still considerable controversy surrounding this move, with claims made of coercion and deceit on the part of the colonial authorities.

The park is Tanzania's oldest national park and remains the

flagship of the country's tourism industry, providing a major draw to

the Northern Safari Circuit encompassing Lake Manyara National Park, Tarangire National Park, Arusha National Park and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. It has over 2,500 lions and more than 1 million wildebeest.

The park is Tanzania's oldest national park and remains the

flagship of the country's tourism industry, providing a major draw to

the Northern Safari Circuit encompassing Lake Manyara National Park, Tarangire National Park, Arusha National Park and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. It has over 2,500 lions and more than 1 million wildebeest.

Geology

The Basement complex consists of Archaen Nyanzian System greenstones (2.81-2.63 Ga in age), Archaean granite-gneiss plutons (2.72-2.56 Ga in age), which were uplifted 180 Ma ago) forming koppies and elongated hills, the Neoproterozoic Mozambique Belt consisting of quartzite or granite, and the Neoproterozoic Ikorongo Group, consisting of sandstone, shale and siltstone that form linear ridges. The southeast portion of the park contains Ngorongoro Neogene-aged volcanics, and Oldoinyo Lengai Holocene-aged volcanic ash. The Grometi, Mara, Mbalageti, and Orangi rivers flow westward to Lake Victoria, while the Oldupai River flows eastward into the Olbalbal Swamps.The park is usually described as divided into three regions-

Serengeti plains: the almost treeless grassland of the south is

the most emblematic scenery of the park. This is where the wildebeest

breed, as they remain in the plains from December to May. Other hoofed

animals - zebra, gazelle, impala, hartebeest, topi, buffalo, waterbuck

- also occur in huge numbers during the wet season. "Kopjes" are

granite florations that are very common in the region, and they are

great observation posts for predators, as well as a refuge for hyrax and pythons.

A hippopotamus walking on the grass land in Serengeti National Park in the morning

Western corridor: the black clay soil covers the savannah of this region. The Grumeti River and its gallery forests is home to Nile crocodiles, patas monkeys, hippopotamus, and martial eagles. The migration passes through from May to July.

Wildebeest on the main highway of the Western Corridor

Human habitation is forbidden in the park with the exception of staff for the Tanzania National Parks Authority, researchers and staff of the Frankfurt Zoological Society,

and staff of the various lodges, campsites and hotels. The main

settlement is Seronera, which houses the majority of research staff and

the park's main headquarters, including its primary airstrip.

Human habitation is forbidden in the park with the exception of staff for the Tanzania National Parks Authority, researchers and staff of the Frankfurt Zoological Society,

and staff of the various lodges, campsites and hotels. The main

settlement is Seronera, which houses the majority of research staff and

the park's main headquarters, including its primary airstrip.

Established: 1951

The park is worldwide known for its abundance of wildlife and high biodiversity.

The migratory -and some resident- wildebeest,

which number over 2 million individuals, constitute the largest

population of big mammals that still roam the planet. They are joined in

their journey through the Serengeti - Mara ecosystem by 250,000 plains zebra, half a million Thomson's and Grant's gazelle, and tens of thousands of topi and Coke's hartebeest. Masai giraffe, waterbuck, impala, warthog and hippo are also abundant. Some rarely seen species of antelope are also present in Serengeti National Park, such as common eland, klipspringer, roan antelope, bushbuck, greater kudu, fringe-eared oryx and dik dik.

Perhaps the most popular animals among tourists are the Big Five, which include:

Lion:

the Serengeti is believed to hold the largest population of lions in

Africa due in part to the abundance of prey species. More than 3,000

lions live in this ecosystem.

Lion:

the Serengeti is believed to hold the largest population of lions in

Africa due in part to the abundance of prey species. More than 3,000

lions live in this ecosystem.African leopard: these reclusive predators are commonly seen in the Seronera region but are present throughout the national park with the population at around 1,000.

African bush elephant: the herds have recovered successfully from population lows in the 1980s caused by poaching, numbering over 5,000 individuals, and are particularly numerous in the northern region of the park.

Eastern black rhinoceros: mainly found around the kopjes in the centre of the park, very few individuals remain due to rampant poaching. Individuals from the Masai Mara Reserve cross the park border and enter Serengeti from the northern section at times. There's currently a small but stable population of 31 individuals left in the park.

African buffalo: the most numerous of the Big Five, with around 53,000 individuals inside the park.

Carnivores -aside from the Big Five- include the 225 cheetah- which is widely seen due to the abundance of gazelle -, about 3,500 spotted hyena, two species of jackals, African golden wolf, honey badger, striped hyena, serval, seven species of mongooses, two species of otters and the East African wild dog of 300 individuals, which recently reintroduced (locally extinct since 1991).

Apart from the safari staples, primates such as yellow and olive baboons and vervet monkey, patas monkey, black-and-white colobus are also seen in the gallery forests of the Grumeti River.

Other mammals include aardvark, aardwolf, bat-eared fox, ground pangolin, crested porcupine, three species of hyraxes and cape hare.

Serengeti National Park has also great ornithological interest, boasting about more than 500 bird species; including Masai ostrich, secretarybird, kori bustards, helmeted guineafowls, southern ground hornbill, crowned cranes, marabou storks, yellow-billed stork, lesser flamingo, martial eagles, lovebirds, oxpeckers, and many species of vultures.

Reptiles in Serengeti National Park include Nile crocodile, leopard tortoise, serrated hinged terrapin, rainbow agama, Nile monitor, chameleons, African python, black mamba, black-necked spitting cobra, puff adder.

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit together with Maasai Mara National Reserve and a lion stronghold in East Africa-

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit together with Maasai Mara National Reserve and a lion stronghold in East Africa-

Administration and protection

Because of its biodiversity and ecological significance, the park has been listed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization as a World Heritage Site. As a national park, it is designated as a Category II protected area under the system developed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature,

which means that it should be managed, through either a legal

instrument or another effective means, to protect the ecosystem or

ecological processes as a whole.

The administrative body for all parks in Tanzania is the Tanzania National Parks Authority. Myles Turner was one of the park's first game wardens and is credited with bringing its rampant poaching under control. His autobiography, My Serengeti Years: The Memoirs of an African Game Warden,

provides a detailed history of the park's early years.

"Snapshot Serengeti" is a science project by the University of Minnesota Lion Project, which seeks to classify over 30 species of animals within the park using 225 camera traps to better understand how they interact with each other and lions.

Proposed road across the northern Serengeti

In July 2010, President Jakaya Kikwete renewed his support for an upgraded road through the northern portion of the park to link Mto wa Mbu, southeast of Ngorongoro Crater, and Musoma on Lake Victoria.

While he said that the road would lead to much-needed development in

poor communities, others, including conservation groups and foreign

governments like Kenya, argued that the road could irreparably damage the great migration and the park's ecosystem.

The African Network for Animal Welfare sued the Tanzanian government in December 2010 at the East African Court of Justice in Arusha

to prevent the road project. The court ruled in June 2014 that the plan

to build the road was unlawful because it would infringe the East African Community Treaty

under which member countries must respect protocols on conservation,

protection, and management of natural resources. The court, therefore,

restrained the government from going ahead with the project.

The African Network for Animal Welfare sued the Tanzanian government in December 2010 at the East African Court of Justice in Arusha

to prevent the road project. The court ruled in June 2014 that the plan

to build the road was unlawful because it would infringe the East African Community Treaty

under which member countries must respect protocols on conservation,

protection, and management of natural resources. The court, therefore,

restrained the government from going ahead with the project.

Proposed extension of park boundaries to Lake Victoria

Government officials have proposed expanding the Serengeti National Park to reach Lake Victoria because increasingly intense droughts are threatening the survival of millions of animals.

MOUNT KILIMANJARO NATIONAL PARK

Kilimanjaro

National Park, in the East African country of Tanzania, is home to the

continent's highest mountain, snowcapped Mt. Kilimanjaro. Around the

base of its tallest peak, relatively accessible hiking trails wind

through rainforest inhabited by colobus monkeys and past the volcanic

caldera of Lake Chala. Approaching the summit of Uhuru Peak, the slopes

steepen and are studded with glacial ice fields.

Kilimanjaro

National Park, in the East African country of Tanzania, is home to the

continent's highest mountain, snowcapped Mt. Kilimanjaro. Around the

base of its tallest peak, relatively accessible hiking trails wind

through rainforest inhabited by colobus monkeys and past the volcanic

caldera of Lake Chala. Approaching the summit of Uhuru Peak, the slopes

steepen and are studded with glacial ice fields.

Kilimanjaro National Park is a Tanzanian national park, located 300 kilometers (190 mi) south of the equator and in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania. The park is located near the city of Moshi.The park includes the whole of Mount Kilimanjaro above the tree line and the surrounding montane forest belt above 1,820 metres (5,970 ft).It covers an area of 1,688 square kilometers (652 sq mi), 2°50'–3°10'S latitude, 37°10'–37°40'E longitude.The park is administered by the Tanzania National Parks Authority (TANAPA).

The park generated US $51 million in revenue in 2013,the second-most of any Tanzanian national park, and was one of only two Tanzanian national parks to generate a surplus during the 2012-13 budget year. (The Ngorongoro Conservation Area,

which includes the heavily visited Ngorongoro Crater, is not a national

park.) The fees for park usage and for climbing Mount Kilimanjaro

during the 2015-16 budget year are published on the Internet. TNPA has reported that the park recorded 58,460 tourists during the 2012-13 budget year, of whom 54,584 were foreigners.Of the park's 57,456 tourists during the 2011-12 budget year, 16,425

hiked the mountain, which was well below the capacity of 28,470 as

specified in the park's General Management Plan.

History

In the early twentieth century, Mount Kilimanjaro and the adjacent forests were declared a game reserve by the German colonial government. In 1921, it was designated a forest reserve.\In 1973, the mountain above the tree line (about 2,700 metres (8,900 ft)) was reclassified as a national park. The park was declared a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in 1987.In 2005, the park was expanded to include the entire montane forest, which had been part of the Kilimanjaro Forest Reserve.

History

In the early twentieth century, Mount Kilimanjaro and the adjacent forests were declared a game reserve by the German colonial government. In 1921, it was designated a forest reserve.\In 1973, the mountain above the tree line (about 2,700 metres (8,900 ft)) was reclassified as a national park. The park was declared a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in 1987.In 2005, the park was expanded to include the entire montane forest, which had been part of the Kilimanjaro Forest Reserve.

Fauna

A variety of animals can be found in the park. Above the timberline, the Kilimanjaro tree hyrax, the grey duiker, and rodents are frequently encountered.[3] The bushbuck and red duiker appear above the timberline in places.[3]Cape buffaloes are found in the montane forest and occasionally in the moorland and grassland.[3]Elephants can be found between the Namwai and Tarakia rivers and sometimes occur at higher elevations.[3] In the montane forests, blue monkeys, western black and white colobuses, bushbabies, and leopards can be found.[

MIKUMI NATIONAL PARK

Area: 1,247 mi²

The landscape of Mikumi is often compared to that of the Serengeti.

The road that crosses the park divides it into two areas with partially

distinct environments. The area north-west is characterized by the

alluvial plain of the river basin Mkata. The vegetation of this area

consists of savannah dotted with acacia, baobab, tamarinds, and some rare palm.

In this area, at the furthest from the road, there are spectacular rock

formations of the mountains Rubeho and Uluguru. The southeast part of

the park is less rich in wildlife, and not very accessible.

The fauna includes many species characteristic of the African

savannah. According to local guides at Mikumi, chances of seeing a lion

who climbs a tree trunk is larger than in Manyara (famous for being one

of the few places where the lions exhibit this behavior). The park

contains a subspecies of giraffe that biologists consider the link

between the Masai giraffe and the reticulated or Somali giraffe.

Other animals in the park are elephants, zebras, impala, eland, kudu,

black antelope, baboons, wildebeests and buffaloes. At about 5 km from

the north of the park, there are two artificial pools inhabited by

hippos. More than 400 different species of birds also inhabit the park.

The fauna includes many species characteristic of the African

savannah. According to local guides at Mikumi, chances of seeing a lion

who climbs a tree trunk is larger than in Manyara (famous for being one

of the few places where the lions exhibit this behavior). The park

contains a subspecies of giraffe that biologists consider the link

between the Masai giraffe and the reticulated or Somali giraffe.

Other animals in the park are elephants, zebras, impala, eland, kudu,

black antelope, baboons, wildebeests and buffaloes. At about 5 km from

the north of the park, there are two artificial pools inhabited by

hippos. More than 400 different species of birds also inhabit the park.

The Mikumi belongs to the circuit of the wildlife parks of Tanzania, less visited by international tourists and better protected from the environmental point of view. Most of the routes that cross the Mikumi proceed in the direction of the Ruaha National Park and the Selous. The recommended season for visiting the park is the dry season between May and November, warm weather and beautiful sites that are a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Territory

The Mikumi is bordered to the south with the Selous Game Reserve,[2] the two areas forming a unique ecosystem. Two other natural areas bordering the national park are the Udzungwa Mountains and Uluguru Mountains.Flora and fauna

A group of baobab trees in the Mikumi National Park, Tanzania.

The fauna includes many species characteristic of the African

savannah. According to local guides at Mikumi, chances of seeing a lion

who climbs a tree trunk is larger than in Manyara (famous for being one

of the few places where the lions exhibit this behavior). The park

contains a subspecies of giraffe that biologists consider the link

between the Masai giraffe and the reticulated or Somali giraffe.

Other animals in the park are elephants, zebras, impala, eland, kudu,

black antelope, baboons, wildebeests and buffaloes. At about 5 km from

the north of the park, there are two artificial pools inhabited by

hippos. More than 400 different species of birds also inhabit the park.

The fauna includes many species characteristic of the African

savannah. According to local guides at Mikumi, chances of seeing a lion

who climbs a tree trunk is larger than in Manyara (famous for being one

of the few places where the lions exhibit this behavior). The park

contains a subspecies of giraffe that biologists consider the link

between the Masai giraffe and the reticulated or Somali giraffe.

Other animals in the park are elephants, zebras, impala, eland, kudu,

black antelope, baboons, wildebeests and buffaloes. At about 5 km from

the north of the park, there are two artificial pools inhabited by

hippos. More than 400 different species of birds also inhabit the park.

The Mikumi belongs to the circuit of the wildlife parks of Tanzania, less visited by international tourists and better protected from the environmental point of view. Most of the routes that cross the Mikumi proceed in the direction of the Ruaha National Park and the Selous. The recommended season for visiting the park is the dry season between May and November, warm weather and beautiful sites that are a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

MKOMAZI NATIONAL PARK

Mkomazi National Park is located in northeastern Tanzania on the Kenyan border, in Kilimanjaro Region and Tanga Region. It was established as a game reserve in 1951 and upgraded to a national park in 2006.[2]

The park covers over 3,234 square kilometres (323,400 ha), and is dominated by Acacia-Commiphora vegetation; it is contiguous with Kenya's Tsavo West National Park. The area commonly called 'Mkomazi' is actually the union of two previous game reserves, the Umba Game Reserve in the east (in Lushoto District, Tanga Region) and the Mkomazi Game Reserve in the west (in Same District, Kilimanjaro Region);

in government documents they are sometimes called the Mkomazi-Umba Game

Reserves. Of the two, Mkomazi is larger, and has more diversity of

relief and habitat, and a longer shared border with Tsavo West National Park. In the rest of this entry, 'Mkomazi' will refer to both the Mkomazi and Umba reserves together. The park covers over 3,234 square kilometres (323,400 ha), and is dominated by Acacia-Commiphora vegetation; it is contiguous with Kenya's Tsavo West National Park. The area commonly called 'Mkomazi' is actually the union of two previous game reserves, the Umba Game Reserve in the east (in Lushoto District, Tanga Region) and the Mkomazi Game Reserve in the west (in Same District, Kilimanjaro Region);

in government documents they are sometimes called the Mkomazi-Umba Game

Reserves. Of the two, Mkomazi is larger, and has more diversity of

relief and habitat, and a longer shared border with Tsavo West National Park. In the rest of this entry, 'Mkomazi' will refer to both the Mkomazi and Umba reserves together.

History of contestLike many national parks and game reserves, Mkomazi's history is one of contest, with the main contenders being government conservation planners and local rural resources users. It differs from many other cases in East Africa because limited resource use within the reserve was initially permitted. When Mkomazi was first established a number of pastoral families from the Parakuyo ethnic group were allowed to continue to live there with a few thousand of their cattle, goats and sheep. The (colonial) government of the time permitted them to reside there because they had been in the area for many years and were thought not to threaten the ecological integrity of the reserve. The pastoralists were only allowed in the eastern half of the reserve. Immigrant Maasai pastoralists and families from other ethnic groups were evicted when the reserve was established.However Mkomazi was soon subject to immigration by other herders, some of which was resisted by the Parakuyo residents, and some which was facilitated by them. What with resident stock breeding and immigrant stock joining the reserve, the first decades of Mkomazi’s history were dominated by rising cattle populations. Some 20,000 animals were counted in the eastern half of the reserve in the early 1960s. In the early 1970s pastoralists began living and grazing in the western half of the reserve and by the mid-1980s around 80,000 cattle were counted inside the reserve as a whole. There were probably thousands more using it intermittently. Many of the immigrants were Maasai, who are very closely related to the Parakuyo, speaking the same language and sharing many customs. But local herders from other ethnic groups, such as the Sambaa and Pare, also grazed thousands of cattle inside Mkomazi. The quantities of cattle within the reserve caused considerable concern for the environment and there was continual pressure to have them evicted. In the late 1980s the government resolved to cease all grazing permission within Mkomazi and evicted all herders. By July 1988 these evictions were complete. Evicted Maasai and Parakuyo pastoralists contested the legality of the evictions, claiming customary rights to the reserve in the Tanzanian courts, but lost their case. After the evictions the British charity, the George Adamson Wildlife Preservation Trust and its American sister charity, the Tony Fitzjohn, George Adamson African Wildlife Preservation Trust became interested in Mkomazi, and have since been spearheading a campaign to restore the reserve. They have set up fenced sanctuaries for African wild dog and black rhinoceros, and are restoring the reserve's infrastructure and supporting local communities with its outreach program me. RepresentationsThe reserve is still subject to illegal incursions from pastoralists, particularly in the wet season. But the main contests about Mkomazi today concern its representation (as comments on this entry may shortly demonstrate). Generally speaking there are two broad camps:For many conservationists, Mkomazi is a celebrated success story. A reserve which was threatened by people and grazing has been restored to good health. The compounds for African wild dog, and the extensive, patrolled sanctuary for the black rhinoceros (which are breeding) have put the reserve on the map, giving it international recognition. Roads have been regraded, dams dredged and rangers kitted out with good uniforms and radios. Anti-poaching patrols restrict incursions by hunters and pastoralists. The work with schools and support for other local needs strengthens relationships with local communities. A high-end tourist safari company has recently announced plans to set up regular holiday safaris to Mkomazi, which will generate more revenue from it and for it. Advocates of Mkomazi see it is a wonderful case of winning back lands for conservation which had been threatened by human interference. Few of Mkomazi's critics can dispute the facts of the previous paragraph, but for them it is simply not the whole story. They resent pro-conservation literature which failed to mention or passed over the evictions and denied former residents' long association with the land. They know the reserve as a place from which thousands of herders were evicted, with inadequate compensation for a few and for most none. They feel that outreach programmes’ benefits do not match the costs of eviction, that many evictees do not benefit from them, and that the numbers of people around the reserve (over 50,000) make it hard to provide meaningful benefits for most locals. They believe the ecological case for eviction is weak - it was often made without any supporting data. Critics of Mkomazi see another sad case of conservation separating people from land. This is not the restoration of wilderness, for none had in fact existed, rather its pristineness has been created and imposed. Despite their stark differences, the two versions of the reserve flourish independently in separate habitats and rarely collide. The positive aspects of Mkomazi's conservation is repeatedly championed in diverse campaigns and fund-raisers, winning international support, awards and celebrity endorsement. It raises hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. Critical perspectives thrive in university courses' teaching material, anthropological and human rights circles, and among conservationists who advocate inclusive approaches to conservation. Here Mkomazi is becoming a benchmark case of how not to evict local people. It is one of the few protected areas for which the costs of eviction and the impoverishment resulting from conservation policies has been rigorously documented. Compromise positions have been offered. Some observers argued that there is the ecological space to allow for a compromise which includes grazing inside Mkomazi. This is legally possible in Tanzania inside game reserves theoretically, but it would only have been realistic in the east as pastoral immigration was often unpopular in the western half. However since Mkomazi has been upgraded to full national park status, which precludes all local use, this is no longer an option. Mkomazi seems destined to be a place about which two very different stories will always be told. Fauna

|

SAADANI NATIONAL PARK

Saadani

National Park is Tanzania's 13th National Park. Tourists can view

animals basking along the Indian Ocean shores. It has an area of 1062

km2 and was officially gazetted in 2005, from a game reserve which had

existed from 1969. It is the only wildlife sanctuary in Tanzania

bordering the sea.

Saadani's

wildlife population is increasing during recent years after it has been

gazetted as a National Park and was a hunting block beforehand.

Wildlife in Saadani includes four of the Big Five, namely lions, African bush elephants, Cape buffaloes and leopards. Masai giraffes, Lichtenstein's hartebeest, waterbucks, blue wildebeests, bohor reedbucks, common and red duikers, Dik-Diks, yellow baboons, vervet monkeys, blue monkeys, Colobus monkeys, mongooses, genets, porcupines, sable antelopes, warthogs, hippopotamuses, crocodiles, nile monitors are also found in the park.

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit.[3]

As such, conservation interventions in the Saadani landscape have taken place since the mid-1960s and have been supported by villagers traditionally inhabiting the Saadani landscape, but it is only recently that state-managed conservation has become a growing concern among the villages adjacent to the park.

In the late 1990s, Mr. Domician Njao, from Tanzania National Parks Authority (TANAPA) came in to "upgrade" the reserve to a National Park, and create the first and only coastal national park of Tanzania. In doing so, park authorities redrew the boundaries of the reserve to include Uvinje’s and Porokanya’s prime coastal lands as if they have always been a part of the reserve [in so doing changing the agreement with those villagers]. Compelling research[4] shows how after this TANAPA proceeded to gazette most of Saadani’s coastal lands as part of the Saadani National Park in 2005, arguing that they have always being a part of the former reserve and belonged to the Park. Spatial analysis on the area of the former Saadani Game reserve, illustrates TANAPA's strategy to gazette Saadani's prime coastal lands as if they have always been a part of the SGR (See various maps of the SGR)

The total extent of SGR is said to have been approximately 209 km²,

however, the SGR official gazette document states that it comprised

approximately 300 km²,while some of TANAPA’s official documents indicate it was 260 km² .

Spatial analysis conducted as part of the present research suggest that

the total game reserve area was of about 200Km2

The vagueness of the language used in the reserve’s official gazette,but also TANAPA’s early interventions to develop its own map of the reserve, and its interests in Saadani’s sub-villages’ prime coastal lands have come to challenge Saadani’s coastal sub-villages’ rights to lawfully inhabit their traditional territories, and have led to chronic political and other battles to demand presently gazetted park lands rescinded, the reestablishment of land rights to traditional inhabitants, and to demand from TANAPA to honour commitments made earlier by Wildlife Division.

In summary, the SNP boundaries and lands have been officially contested[6] by District authorities and no less than 6 villages, while at least 4 adjacent villages are engaged in higher level advocacy to have park boundaries reassessed. However, of all the villages, it is Saadani which faces the greatest challenges on the gazetting of a large part of its coastal territory which, by all accounts, has been done unilaterally. Saadani is also the village with the largest strip of coastal land.

At present, and after more than a decade of institutional struggles, Saadani village has resisted TANAPA’s various approaches to take possession of the now sub-village’s gazetted territory and have consistently demanded that their land rights be restored, and continue to reiterate that they are not going to give their traditional territory for any amount of compensation money. Such community assertions and actions certainly challenge traditional conceptions of economic gain as the central motivation in park community-conflicts, and suggest that deeply rooted spatial-cultural territorial connections are as essential as and perhaps even more important to people's collective welfare than material benefits.

To this day, park governance and management approaches have been unable to gain the support of surrounding villages, which traditionally have been very conservation minded, for addressing poaching and for collaboratively sustaining landscape level conservation efforts. All of which are desperately needed to combat the sevenfold increase in poaching activity being faced by the park in the last seven years. No less than 10 of the 17 villages adjacent to the park have their own community-conserved areas, equivalent to no less than 20% of area identified as park lands. Despite the level of environmental awareness of these adjacent villages and the importance of corridors and ecosystem connectivity to successful ecological conservation, the villages’ conservation efforts have not been linked to park efforts but at present represent a threat to park authorities. For park authorities, it is within villages’ conserved areas where more often than not poaching is seen to be taking place.

Wildlife

Wildlife

Saadani's

wildlife population is increasing during recent years after it has been

gazetted as a National Park and was a hunting block beforehand.

Wildlife in Saadani includes four of the Big Five, namely lions, African bush elephants, Cape buffaloes and leopards. Masai giraffes, Lichtenstein's hartebeest, waterbucks, blue wildebeests, bohor reedbucks, common and red duikers, Dik-Diks, yellow baboons, vervet monkeys, blue monkeys, Colobus monkeys, mongooses, genets, porcupines, sable antelopes, warthogs, hippopotamuses, crocodiles, nile monitors are also found in the park.

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit.[3]

History

Gazetted in 2005, it encompasses a preserved ecosystem including the former Saadani game reserve, the former Mkwaja ranch area, the Wami River as well as the Zaraninge Forest. In the late 1960s Saadani Village – the village after which the park has been named – and particularly its sub-village Uvinje, invited the Tanzania Wildlife Division (WD) to help them to prevent the indiscriminate killing of wildlife prevalent in the area. From this partnership Saadani village and the Wildlife Division established the Saadani Game Reserve (SGR), with the agreement to respect the land rights of the coastal sub-villages of Saadani, including Uvinje and Porokanya sub-villages, while also addressing the needs of wildlife.As such, conservation interventions in the Saadani landscape have taken place since the mid-1960s and have been supported by villagers traditionally inhabiting the Saadani landscape, but it is only recently that state-managed conservation has become a growing concern among the villages adjacent to the park.

In the late 1990s, Mr. Domician Njao, from Tanzania National Parks Authority (TANAPA) came in to "upgrade" the reserve to a National Park, and create the first and only coastal national park of Tanzania. In doing so, park authorities redrew the boundaries of the reserve to include Uvinje’s and Porokanya’s prime coastal lands as if they have always been a part of the reserve [in so doing changing the agreement with those villagers]. Compelling research[4] shows how after this TANAPA proceeded to gazette most of Saadani’s coastal lands as part of the Saadani National Park in 2005, arguing that they have always being a part of the former reserve and belonged to the Park. Spatial analysis on the area of the former Saadani Game reserve, illustrates TANAPA's strategy to gazette Saadani's prime coastal lands as if they have always been a part of the SGR (See various maps of the SGR)

Tanapa's Map of the SGR created between 1999 and 2001.png 29 KB

SGR Map Outcome of Doctoral Research.png 53 KB

SGR Map from University of Dar es Salaam map template from 1996.png 240 KB

SGR

Maps combined. Either UDar_1996 or current doctoral research SGR maps

include Saadani's prime coastal lands. However,TANAPA's map version of

the SGR has 3/4 of Saadani's village coastal lands included as part of

the SGR.

The vagueness of the language used in the reserve’s official gazette,but also TANAPA’s early interventions to develop its own map of the reserve, and its interests in Saadani’s sub-villages’ prime coastal lands have come to challenge Saadani’s coastal sub-villages’ rights to lawfully inhabit their traditional territories, and have led to chronic political and other battles to demand presently gazetted park lands rescinded, the reestablishment of land rights to traditional inhabitants, and to demand from TANAPA to honour commitments made earlier by Wildlife Division.

The Current Status of Saadani National Park

By law, setting aside areas for conservation has to be consulted on, at least to some extent, with affected villages. However, it was not until late in 2005 that the village of Saadani and leaders of its Uvinje sub-village realized that the full extent of Uvinje’s lands were gazetted as part of the park. This despite numerous communications taking place since the early 2000s where village leaders continuously reiterate that Uvinje lands have never been a part of the reserve and that they will not vacate their lands . Important park establishment documents illustrate that TANAPA’s argument for gazetting lands from two Saadani coastal sub-villages is that they have always being part of the former game reserve, an argument that seem to have allowed them to move forward gazetting the coastal lands without coming to an agreement with the leaders at that time, who have reiterated that they did not agree to giving coastal lands to TANAPA.In summary, the SNP boundaries and lands have been officially contested[6] by District authorities and no less than 6 villages, while at least 4 adjacent villages are engaged in higher level advocacy to have park boundaries reassessed. However, of all the villages, it is Saadani which faces the greatest challenges on the gazetting of a large part of its coastal territory which, by all accounts, has been done unilaterally. Saadani is also the village with the largest strip of coastal land.

At present, and after more than a decade of institutional struggles, Saadani village has resisted TANAPA’s various approaches to take possession of the now sub-village’s gazetted territory and have consistently demanded that their land rights be restored, and continue to reiterate that they are not going to give their traditional territory for any amount of compensation money. Such community assertions and actions certainly challenge traditional conceptions of economic gain as the central motivation in park community-conflicts, and suggest that deeply rooted spatial-cultural territorial connections are as essential as and perhaps even more important to people's collective welfare than material benefits.

To this day, park governance and management approaches have been unable to gain the support of surrounding villages, which traditionally have been very conservation minded, for addressing poaching and for collaboratively sustaining landscape level conservation efforts. All of which are desperately needed to combat the sevenfold increase in poaching activity being faced by the park in the last seven years. No less than 10 of the 17 villages adjacent to the park have their own community-conserved areas, equivalent to no less than 20% of area identified as park lands. Despite the level of environmental awareness of these adjacent villages and the importance of corridors and ecosystem connectivity to successful ecological conservation, the villages’ conservation efforts have not been linked to park efforts but at present represent a threat to park authorities. For park authorities, it is within villages’ conserved areas where more often than not poaching is seen to be taking place.

MAHALE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK

Mahale

Mountains National Park lies on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in Kigoma

Region, Tanzania. Named after the Mahale Mountains range that is within

its borders, the park has several unusual characteristics. First, it is

one of only two protected areas for chimpanzees in the country.

Mahale Mountains National Park lies on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in Kigoma Region, Tanzania. Named after the Mahale Mountains range that is within its borders, the park has several unusual characteristics. First, it is one of only two protected areas for chimpanzees in the country. (The other is nearby Gombe Stream National Park made famous by the researcher Jane Goodall.) The chimpanzee population in Mahale Mountains National Park is the largest known and due to its size and remoteness, the chimpanzees flourish. It also the only place where chimpanzees and lions co-exist. Another unusual feature of the park is that it is one of the very few in Africa that must be experienced by foot. There are no roads or other infrastructure within the park boundaries, and the only way in and out of the park is via boat on the lake.

The Mahale mountains were traditionally inhabited by the Batongwe and Holoholo people, with populations in 1987 of 22,000 and 12,500 respectively. When the Mahale Mountains Wildlife Research Center was established in 1979 these people were expelled from the mountains to make way for the park, which opened in 1985. The people had been highly attuned to the natural environment, living with virtually no impact on the ecology.[2]

RUAHA NATIONAL PARK

Ruaha

National Park is the largest national park in Tanzania. The addition of

the Usangu Game Reserve and other important wetlands to the park in

2008 increased its size to about 20,226 square kilometres, making it the

largest park in Tanzania and East Africa.

The park is about 130 kilometres west of Iringa.

Ruaha National Park is the largest national park in Tanzania.

The addition of the Usangu Game Reserve and other important wetlands to

the park in 2008 increased its size to about 20,226 square kilometres

(7,809 sq mi), making it the largest park in Tanzania and East Africa.

Ruaha National Park is the largest national park in Tanzania.

The addition of the Usangu Game Reserve and other important wetlands to

the park in 2008 increased its size to about 20,226 square kilometres

(7,809 sq mi), making it the largest park in Tanzania and East Africa.

The park is about 130 kilometres (81 mi) west of Iringa. The park is a part of the 45,000 square kilometres (17,000 sq mi) Rungwa-Kizigo-Muhesi ecosystem, which includes the Rungwa Game Reserve, the Kizigo and Muhesi Game Reserves, and the Mbomipa Wildlife Management Area.

The name of the park is derived from the Great Ruaha River, which flows along its southeastern margin and is the focus for game-viewing. The park can be reached by car on a dirt road from Iringa and there are two airstrips – Msembe airstrip at Msembe (park headquarters), and Jongomeru Airstrip, near the Jongomeru Ranger Post.

More than 571 species of birds have been identified in the park. Among the resident species are hornbills.[2] Many migratory birds visit the park.[2]

Other noted animals found in this park are East African cheetah[4] and lion, African leopard and wild dog, spotted hyena, giraffe, hippopotamus, African buffalo, and sable antelope.[2][5]

Since 2005, the protected area is considered a Lion Conservation Unit.[6]

Ruaha National Park is the largest national park in Tanzania.

The addition of the Usangu Game Reserve and other important wetlands to

the park in 2008 increased its size to about 20,226 square kilometres

(7,809 sq mi), making it the largest park in Tanzania and East Africa.

Ruaha National Park is the largest national park in Tanzania.

The addition of the Usangu Game Reserve and other important wetlands to

the park in 2008 increased its size to about 20,226 square kilometres

(7,809 sq mi), making it the largest park in Tanzania and East Africa.

The park is about 130 kilometres (81 mi) west of Iringa. The park is a part of the 45,000 square kilometres (17,000 sq mi) Rungwa-Kizigo-Muhesi ecosystem, which includes the Rungwa Game Reserve, the Kizigo and Muhesi Game Reserves, and the Mbomipa Wildlife Management Area.

The name of the park is derived from the Great Ruaha River, which flows along its southeastern margin and is the focus for game-viewing. The park can be reached by car on a dirt road from Iringa and there are two airstrips – Msembe airstrip at Msembe (park headquarters), and Jongomeru Airstrip, near the Jongomeru Ranger Post.

History and wildlife